Two old cricketers left us last week, one well-known, the other less recognisable. They meant something to me because the latter played in the first county championship match I saw at Old Trafford, and the former appeared in my first Test match.

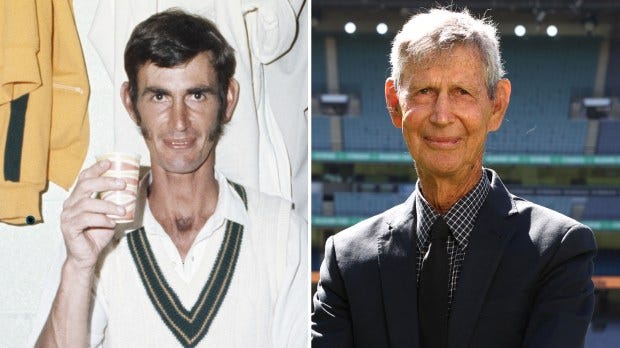

The less recognisable face belonged to Brian Jackson, the Derbyshire fast medium bowler, who died at the age of 91. Ian Redpath, the Australian batsman who played in 66 Tests between 1964 and 1976, was eight years younger. Both men were good representatives of a certain type: Jackson, the steadfast English pro, and Redpath, the flinty Aussie from central casting.

Redpath put a high price on his wicket, as a Test average of 43 indicates. He was an obdurate opener, regarded by John Snow as ‘a real nuisance’. With Bill Lawry, his fellow Victorian at the other end, the bowlers k new they were engaged in a battle of will, though ‘Redders’ had the strokes, too. Rather like Kenny Barrington he became a more conservative batsman as his career progressed.

Jackson was cut from very different cloth. A talented opening bowler with Cheshire in the Minor Counties, he didn’t play county cricket until his 30th year, in 1963. That summer was the first of six he spent with Derbyshire, where he shared the new ball with Harold Rhodes.

I saw Jackson bowl at Old Trafford in June 1967. The match was drawn, and neither side was much cop that year. But the memory is part of a personal mythology, for it was my first visit to a ground which became a significant feature of my young life.

In those days every county had a few men like Jackson. There was little money, and in the winters they were left to their own devices. Many struggled. Yet each April they returned to the scene, pulled on their boots, and put their shoulders to the wheel, happy to play a game they loved.

That’s a sentimental view of a professional game that could be hard on the old troupers. But it’s how many of us grew up. From this distance it’s clear that much of the cricket in the Sixties was dull, and some players wouldn’t have lasted long in the modern dispensation. But we remember those players with affection, because they shaped our perception of cricket.

Jackson’s last summer with Derbyshire in 1968 brought 56 wickets, which was not considered good enough to earn another contract. Last summer only one bowler, Jamie Porter of Essex, took 56 wickets, and his haul was held to be excellent.

How much has changed in half a century. In Jackson’s day the championship was dominant. Now the first-class programme is incidental; something the players get up to when there is no T20 or Hundred to occupy them for a couple of hours. As we have seen with Jacob Bethell, and a few others, it is no longer necessary to have a county record in order to play Test cricket. You can be selected on potential alone.

In six summers of hard graft Jackson took 456 wickets, at an average of 18. Although he bowled on uncovered pitches, and Derby always favoured the seamers, those figures are pretty impressive. In retirement he became a rep for Marston’s, the Burton brewers. Their great ale, Pedigree, is not what it was. It’s a familiar story, in cricket and in so many other things. Poorly paid as he was, Jackson may have thought his generation had the best of it, on and off the field.

Redpath didn’t shine on the Old Trafford stage in 1968. He made 8 and 8, lbw to Snow in both innings. But Australia won the Test convincingly, and were only pegged back when Derek Underwood bowled England to victory at a sodden Oval in the fifth and final match, after Colin Cowdrey had encouraged spectators to help mop up the outfield.

In retirement Redpath ran an antique shop in Geelong. He was a fine batsman, admired for his courage and his commitment to the team. He was an excellent Aussie Rules footballer, too. A true all-rounder.

We have lost two modest men who played the game. And, for some of us, made the game.