Thank You for the Days

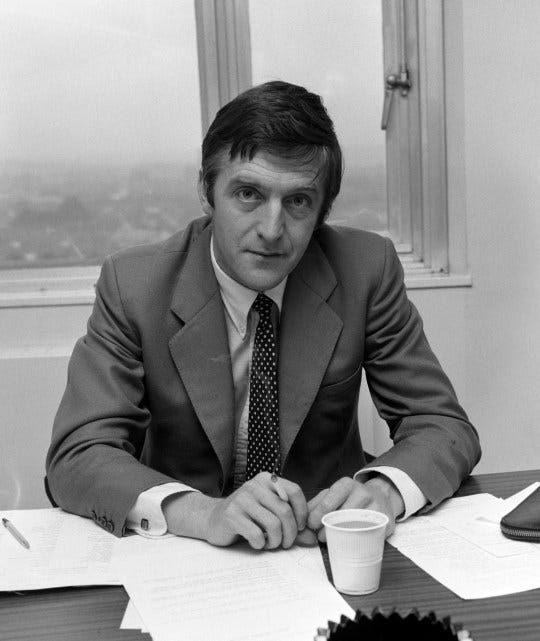

‘I don’t have to believe it if I don’t want to’, John O’Hara said after George Gershwin was recruited for the heavenly choir at the horribly young age of 38. Those who knew Michael Parkinson (disclosure is necessary: he was a friend) may share the novelist’s sentiments.

The news, when it broke on the morning of August 17, was not unexpected. He had been frail for some time, weakened by treatment for prostate cancer and the general pounding of Time’s winged chariot. At such times it is appropriate to say death comes as a merciful release.

Torrents of praise blew in swiftly from every corner of the kingdom. ‘The master interviewer’, people said, and he was. ‘Parkinson’, first screened on Saturday evenings in the summer of 1971, is part of British post-war folklore. It wasn’t the first chat show, but it was the best and, as it turned out, the last. The ones which followed were vehicles for the presenter to drive, usually into the nearest ditch.

Within months it was a mark of distinction to appear on ‘Parky’, at least for the first run, which closed in 1982. When the show was revived in 1998 times had changed, and so had television. There were still some good guests but let’s be honest, it’s a long way from Orson Welles, who lit up that first summer with his cigar and glowing sentences, to the studied banalities of David Beckham.

Parky, pinching himself, met the stars of his youth. Fred Astaire, Lauren Bacall, Jimmy Cagney, Bette Davis, Gene Kelly and James Stewart led the lists in those formative years. Today there are no stars of their magnitude. Yet the programme also found room for John Arlott, Wystan Auden, Jacob Bronowksi, Anthony Burgess and Alistair Cooke, as well as an ‘open return’ for Jonathan Miller. Where are their successors? And who could persuade them to appear?

This tale requires no embroidery. Parky was one of the most significant figures of television’s golden age, before the canker of celebrity and the expansion of channels altered public taste. What is less well-known, certainly among younger people, is how fine a sportswriter he was.

When the third bottle had arrived, and cheese was put on the table, he used to wonder whether he should have concentrated on his writing. He had both, of course: the enlightened monarchy of late night telly, and the writing in his spare time. So there was never any anguish.

Yet the journalist in him did wonder, because at heart he remained the reporter who had begun life on local papers in Yorkshire. The Manchester Guardian and Daily Express then paved the yellow brick road to national recognition before the box claimed his principal loyalty, as producer, then news reporter and finally presenter.

The best all-round sportswriters of his generation were Ian Wooldridge of the Daily Mail, and Hugh McIlvanney in his Observer days. McIlvanney, supreme on boxing, was a beautiful essayist whose prose curdled into self-parody when he moved to the Sunday Times. ‘Woollers’ was always readable; the best of the best.

Frank Keating of the Guardian was also excellent, even if he didn’t always witness the events he wrote about! Like McIlvanney, strong drink took the sheen off his early brilliance. Woollers could leave them both asleep in the snug bar, and still lead the back page.

A chapeau, too, for Simon Barnes of the Times, who was a true original.

As a columnist Parky ranked alongside Patrick Collins of the Mail on Sunday. They both challenged the dullards and sharpies with a wit that didn’t entirely conceal the stiletto that had to be thrust, now and again, between the shoulder-blades.

When he started writing for the Sunday Times in the Sixties he had a young man’s zeal, and Marylebone Cricket Club, which governed his favourite sport, made a good target. MCC was then a very different body to the self-consciously ‘inclusive’ organisation which now appears to be scared of its own shadow. There was genuine snobbery in those days, and Parky went in to bat for all those cricket-lovers who, like him, had not tasted public school and Oxbridge.

In the Nineties, when David Welch invited him to write weekly columns for the Telegraph, Parky cut a senatorial figure. He enjoyed the company of younger men, like Paul Hayward, the paper’s chief sportswriter, who helped to keep him match fit. Like Wooldridge and Keating, he was generous with advice and happy to praise the work of others. Why not? His own reputation stood like Gibraltar.

Cricket, everybody knows, he loved most. He inherited the obsession from his father, John William, who took the family to Scarborough each summer to play with bat and ball on the beach, as families did in those innocent days. Those improvised pitches are now playgrounds for lager-swillers and drug-users. A different world.

As a boy he watched Leonard Hutton bat at Bramall Lane in Sheffield, which was closer to his Cudworth home than Headingley, a ground he never liked. Nor, for all his love of Yorkshire cricket lore, did he warm to some people he met in the committee room. Offered the club presidency in the autumn of his years, he turned it down, ostensibly because he lived in Berkshire but also because he had heard too much over the years from too many mouths, and didn’t care for every word.

He was a cricketer of the heart, who eventually signed a peace treaty with Lord’s. He could be found there every summer for the Test, surrounded by friends from the club at Bray, as well as people like Tom Courtenay and Ronald Harwood, who enjoyed the game almost as much as he did. The ‘Parky box’ was never a showbiz enclave. He thought too much of his friends for that.

Which players fired his imagination? All the Yorkies from his childhood, most of all Fred Trueman: ‘the finest bowling action I have ever seen’. Tom Graveney, the handsome strokemaker for Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, was a favourite. Ian Botham, of course. He knew Geoffrey Boycott from way back in Barnsley, and always backed him, whatever.

Of the more recent stars Shane Warne led the way, though the Australian he loved most, indeed the cricketer he placed at the head of his personal mythology, was Keith Miller. ‘Nugget’ the golden boy represented the soul of cricket, a contest of nobility that should bring out the best in all who played it. Miller played hard, as many a batsman confirmed. He also understood it was only a game, which must never be the most important thing in a person’s life.

Football he cared less for. He had seen Tom Finney and Bobby Moore set standards of grace and humility, and didn’t admire much about the modern game, which is built on pots of money and a deeply entrenched dishonesty. Two Irishmen did most to shape his thinking: Danny Blanchflower, who he watched at Barnsley, playing a different game to those around him; and George Best, the one and only, who became a close friend. He chose his heroes well.

In some ways Parky was the boy who never grew up, bewitched throughout his life by those great stars of the screen, and the singers who adorned the pages of the Great American Songbook. He loved the jazzers, too, beginning, as everybody does, with Louis Armstrong. As he liked to say, you meet a better class of person when you wander down Memory Lane.

So, while he is no longer here, we don’t have to believe it if we don’t want to. We can still read his essays on sport and sportsmen, for pleasure and instruction. He left a lot behind, for which we should be thankful.

Very sad. Older readers will also have fond memories of his references to Skinner Normanton, who was, I recall, in his words, "built like a brick shit house door".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skinner_Normanton

"Normanton was brought to wider notice in the writings of Michael Parkinson"

I shall raise a glass to him tonight!

Lovely piece of writing on a man I had/have great respect for from his early career with Granada onwards. I have always preferred his sports journalism to his TV work. You mention his admiration for Blanchflower and Best. Both great players. You might also add one of the former's great mates, Jimmy Mcilroy at Burnley. Graveney too was a schoolboy idol of mine but I have a faint memory of him saying on a TV interview with, I think, Peter West, that the Pakistan cricket team "have been cheating us for years". This has taken some of the gloss off my sporting memories of the man.