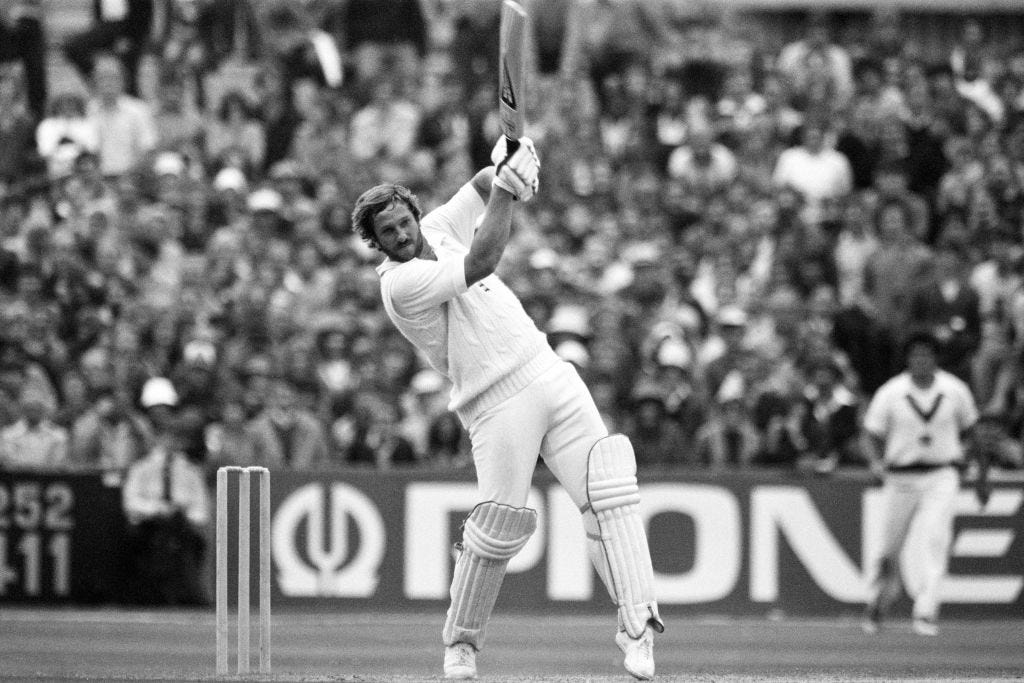

As a taster for the forthcoming Old Trafford Test, Michael reflects on a day at Old Trafford in 1981, witnessing the finest innings by the greatest English cricketer of our lifetimes.

Was it as good as they say?

It was, me duck. No trace of a fib.

‘Spin me back down the years’, as Ian Anderson liked to sing, ‘to the days of my youth’. It certainly feels like youth from this distance, though it was receding like The Raft of the Medusa. Forty two summers we must travel, to a blessed August Saturday at Old Trafford.

England was in turmoil: riots in Liverpool, and general unhappiness. Two years into her reign, Margaret Thatcher was not a popular Prime Minister. We needed cheering up, and nobody who caught the Ashes that summer, either in person or on the telly, will need persuading that something remarkable happened.

The series started dismally at Trent Bridge, where Trevor Chappell, the weakest branch of a distinguished cricketing tree, scored the winning runs. Paul Downton had dropped a catch, and England suffered the consequences. So did Downton. In those days, if the wicketkeeper missed an important catch he was invited to ponder his error in the silence of a lonely room.

At Lord’s, in a drawn second Test, Ian Botham bagged a pair and resigned the captaincy, beating Alec Bedser, chairman of the selectors, to the punch. When they went to Headingley for the third Test, Mike Brearley, restored as captain, asked the champion all-rounder whether he wanted to play.

‘Of course’, Botham replied. And that is where the fun began.

Not immediately. That opening day in Leeds, when John Dyson made an unhurried century, was not one for the annals, though Botham took six wickets. He then made 50 runs briskly in England’s inadequate reply, and when Terry Alderman dismissed Graham Gooch in the first over of the second innings on Saturday evening, those famous odds on an England victory were pasted on Headingley’s electronic scoreboard: 500 to one.

Everybody knows what happened next. Liberated by Brearley’s words, and by the desperation of the situation, Botham blasted a bugger-the-lot-of-you century, before his great friend Bob Willis came charging down the hill in Australia’s second innings to take eight for 43. England won the greatest Test of all by 18 runs.

All over England life stopped, as though somebody had thrown a magic boomerang. There was never a day like that before, and there hasn’t been one since, no matter what you may have read. The frog was a prince again, and a nation rejoiced.

What did Botham do at the end of that tumultuous fourth day, which he ended 145 not out? He lit up a cheroot before he had taken off his pads! Patrick Eagar, Johnny on the spot, took the famous picture which proves it; one of the finest of all sporting photographs.

At Birmingham, the jollity continued. Roared on by thousands of spectators who had come to believe in miracles, Botham was now a match-winner with ball, taking five wickets for one run as Australia’s batsmen were encased in stone. Like us they couldn’t understand what they had witnessed.

Which brings us to the fifth Test, and the greatest performance of all. No miracle this time. More like a communal laying on of hands.

England, batting first, made 231, no great total, and owed 52 of those to Paul Allott, making his Test debut. But their lead was 101 when Australia collapsed in a heap. The third day would be crucial.

Saturday began overcast, and the cricket lacked dazzle. When Chris Tavare, batting like a prophet with no doubts, walked up the pavilion steps at lunchtime after two hours of toil a member stepped out of the ‘pit of hate’ to tell him he was ‘a bloody disgrace’. He was only trying to help England beat Australia!

When Botham joined him after lunch England had lost half their wickets for 104, and their advantage was a precarious 205. Another wicket, and it could be all fall down. So he played himself in thoughtfully. After the lunacy of Leeds, where he had ridden his luck like a bucking bronco, here was a batsman serious in his purpose.

The rabbits came out of the hat when Australia took the new ball. He hooked Dennis Lillee three times for six. The great fast bowler was not the tearaway of younger days, but he was still a considerable force. Terry Alderman, a magnificent swing bowler, saw a ball marginally short of a good length pulled violently over midwicket deep into the bleachers. Botham’s bat sounded like the crack of a whip.

Ray Bright, nicknamed ‘the binman’ by a Lancashire wag on the grounds that ‘every street needs one’, was pummelled for a pair of sixes, the first of which landed in the pit of hate, which had been transformed by Botham’s magic wand into a caravan of love!

What an afternoon that was. In those days you could perch beneath the bell by the entrance to the dressing rooms, and that is where my old schoolfriend Jeremy Ogden and myself took up squatters’ rights. We brushed against the players when they came out, and we cheered Botham all the way home when he was eventually out for 118: the innings of his life, and of ours.

No Englishman, not Hobbs, not Hutton, not Hammond, not Compton, not May, has ever batted with such freedom. They were all undoubtedly finer batsmen but Botham commanded the stage that day like Wotan. His bat was a spear, and his word was writ. In Monday’s Times John Woodcock invited readers to consider the innings as the greatest of all time.

Australia made 405 in their second innings, with Graham Yallop and Allan Border making centuries, so England had need of Botham’s alchemy. The winning margin was 103 runs.

Had Australia won the series would have been balanced at two Tests apiece. Instead the Oval saw a ‘dead’ match, though the curtain did not come down until the maker of miracles, drawing on reserves that had left others breathless, sent down 89 overs for 10 wickets. It was another colossal effort by the most remarkable England cricketer of our lives.

No other could have done what Botham did that summer, and the richest feast belonged to Old Trafford. Andrew Flintoff will always have 2005, when he was indomitable, and Ben Stokes pulled off an extraordinary victory at Headingley four years ago. Their names are in lights. Botham’s is carved in rock.

How freely he shared his bounty with us in 1981. A broken man at Lord’s, he bounced off the ropes with such certainty, and such lack of self-pity, that a nation cheered for him, for England, and for the sheer joy of being alive.

‘You never write anything rude about Beefy’, Mark Nicholas told me some years ago. ‘Other people, yes, but never him’.

Quite true. But why would anybody want to write a rude word about a man who did so much for the game, and, through his efforts off the field, raised so much money that children with cancer of the blood may live? It is a tribute to his spirit that the finest work of his fulfilling life has come in retirement. He makes good wines, too.

John Arlott saw something of his character when Botham was a young professional at Taunton. ‘Help me carry this case up the stairs’, the famous commentator told him, ‘and when we’ve opened a bottle of red wine I’ll show you how to drink it’.

Five decades later we’re still celebrating the health of our all-time champion. And we always will.

The mood was grim, Paul.

Very different at Old Trafford!

Was there as a 10 year old. Ticket was £1, pay on the day.